I am doing a PhD in historical theology (i.e. history + theology) and will spend November researching in the UK. I thought I’d share a number of things about what I’m up to here for those who are interested.

Why study church history?

I plan to explain why church history is important in a future post, but for now here are two good reasons:

(1) To learn from fellow believers from other eras. The Bible teaches us to learn and benefit from other Christians. Just think of how much the Christians through the ages have to teach us! Thankfully many of them left writings behind that we can benefit from. They often have insights in life and the Bible that we don’t, and discuss topics that we didn’t realise were important.

(2) The past has made us who we are in ways that we are mostly not aware of. We can only identify many of our own assumptions and beliefs by looking at where they came from. Why do you do church the way you do, or approach the Bible the way you do, and think about God in the terms, categories and emphases that you do? The answers are found in church history.

I am enjoying what I’m learning for these reasons and more. I am already seeing all kinds of ways in which what I’m learning is benefiting teaching others.

My Research Topic

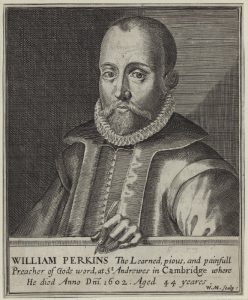

I am studying William Perkins (1558-1602) who was a famous English theologian in the 1590s and into the early 1600s century. Besides England, his writings were also influential in Europe and in New England.

Perkins is remembered as an early Puritan, and he certainly influenced the Puritan movement after him. However, Perkins saw himself as a member of the mainstream. He was of the first generation raised under the Elizabethan settlement of religion (1559), which means that he was raised with the 1559 Book of Common Prayer and official homilies (sermons) in church. What bothered Perkins was that whilst England officially had excellent Reformed theology (enshrined in the 39 Articles of Religion), it was clear to him that most English people were only shallowly ‘Christian’ at best. This is from a sermon Perkins preached in 1593:

‘All men say, they believe, and have repented long agone; but try it well, and we shall finde in the body of our Nation, but a lip-faith,and a lip-repentance: for even when they say so, they are blinde and ignorant of their owne estate, and know not themselves, by presume of themselves, that because they are baptized and live in the Church, therefore they are in Gods favour, and in very good estate; when as they never yet saw any sinnes in themselves whereof they should repent.’

…and as we have Religion so we have it under a religious Prince, whereby it comes to passé, that these blessings of salvation wee enjoy not in secret, or by stealth, but we have it countenanced by authority: so that Religion is not barely allowd, but even as it were thrust upon men. …Who would look for ignorance after thirty five years of preaching? And yet many are as ignorant, as if they had beene borne and brought up under Poperie…

‘An Exhortation to Repentance out of Zephaniah’

Preached at Sturbridge Fair, Cambridge 1593

Perkins’ life’s work centered on addressing the problem of spiritual ignorance and helping people properly apply official church doctrine to themselves in genuine conversion and obedience.

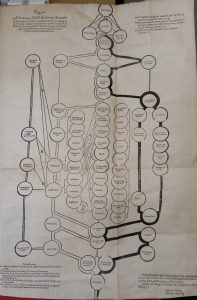

Perkins is probably best remembered today for his teaching on predestination. Whilst he did teach a lot on that topic, it wasn’t his main focus. The main reason he is remembered today is because of his chart of the logic of predestination at the beginning of his early bestseller “A Golden Chain” (1590).

Here’s an overview of the main topics of Perkins’ writings:

Sermons: Perkins preached slowly through Bible books, verse-by-verse, with lots of discussion of doctrine and application. His published sermons cover the temptation of Jesus (Matthew 4:1-11), the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7), Galatians, Hebrews 11, Jude, Revelation 1-3. Various other sermons ended up as short treatises.

Ministry: Perkins was known as a great preacher and wrote the first English language book on the subject (The Art of Prophesying, 1592). He also wrote a book on pastoral ministry (The Calling of the Ministry, 1605).

Catechetical Works: catechesis refer to learning essential Christian doctrine. People were typically taught the 10 Commandments, Lord’s Prayer, and the Apostles’ Creed. Perkins wrote books on the latter two. Most notable is Perkins’ Foundation of Christian Religion (1591) which is a very short question-and-answer approach to six doctrines and how to know them in your heart and not just your head. Perkins recognised that many would rote-learn the creed and not actually apply it to themselves by faith. This excellent little tract was used by adults and children alike.

Conversion: Perkins can be described as a ‘practical predestinarian’, meaning that he expected that God choosing, calling, and converting someone would change how they live. Predestination is a very practical subject related to Christian conduct and assurance. Perkins’ first bestseller was about how you can know you are elect (Whether a man be in a state of damnation or a state of grace, 1588), a theme he returned to regularly. He also wrote academic titles on predestination related to some theological disputes of the mid-1590s: The Manner and Order of Predestination (1596) and God’s Free Grace and Man’s Free Will (1601).

Witchcraft: the renaissance was a very spiritual affair, with a revival in every manner of mystical, spiritual stuff. In the early-modern period (i.e. 1500-1700) science, philosophy, maths, alchemy, and magic were all overlapping topics. Our science is about understanding the physical world; theirs was about understanding the physical and the spiritual as a single system. Before he was converted Perkins himself fell into obsession with the occult. Why? Because he was good at maths! He preached and wrote very forcefully against false spirituality after becoming a Christian, including The Damned Art of Witchcraft (1608), a book against soothsaying & fortunetelling (1585), and two obscure works in Latin against a particular Renaissance philosophy’s view of how memory works (1584). (If you are really interested, it’s called Hermeticism – Google it).

Roman Catholicism: Roman Catholicism was not only what the Reformation rejected, but was a political threat in the Elizabethan era. Not only did the (Catholic) Spanish invade (1588), but the Pope formally authorised any Catholic attempt to overthrow Elizabeth’s rule (1570). Perkins wrote two works against Roman Catholic teaching showing how these two competing faiths differ, and arguing that Protestantism is better supported by the theologians of the early Christian centuries than Roman Catholicism is (A Reformed Catholic, 1597; Problem of the Forged Catholicism, 1604).

Ethics & Christian Decision Making: technically this area is called ‘casuistry’ and is concerned with the right use of our God-given (and Spirit-renewed) consciences to make godly decisions. Perkins was one of the earliest Protestant examples of creating a system of casuistry. His posthumously compiled Whole Treatise of the Cases of Conscience (1604) is seen by some as the pinnacle of his work.

Society: Perkins wrote on themes of daily life, including work (Vocations or Callings of Men, 1603), family (The Right Manner of Erecting & Ordering a Family, 1609), and social equity (Christian Equity & Moderation, 1604).

This list is not comprehensive, but it gives a sense of what Perkins produced. He was very prolific. His works are currently in the process of being published for the first time since the 17th century, and will consist of 41 works in 10 volumes.

Hunting for Sources

Part of doing history properly is tracking down the best sources available. In this amazing era of digitalised records I have digital copies of first editions of almost all of Perkins books, as well as the definitive three-volume edition of his collected works (1626, 1631). However I also need to track down basically every piece of paper that Perkins ever wrote on. I hoped to track down his personal book collection since a lot of people annotated their books in those days and I would have learned a lot about Perkins’ views from what he wrote in book margins. However, after much treasure-hunting, I found that Perkins’ books were looted and dispersed in 1641.

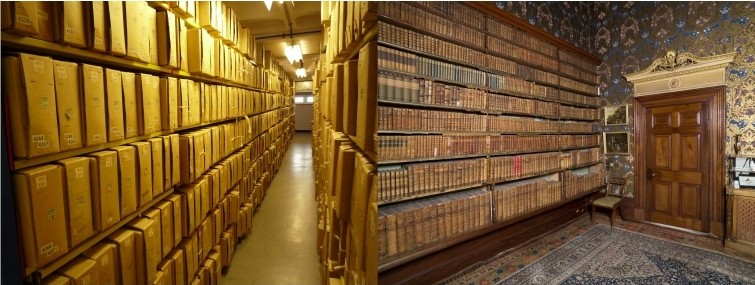

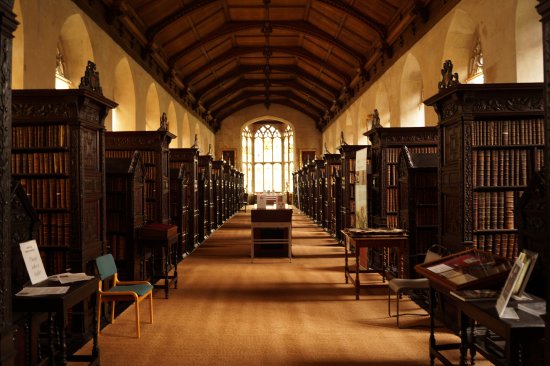

A Cambridge graduate called William Bedell (1571-1642) bought Perkins’ books when he died. Bedell took them to Ireland when he became a bishop there. However there was an Irish uprising and Bedell was imprisoned. When the English came to crush the rebellion the English troops looted whatever they could, including Perkins’ books! Bedell’s son (whose inheritance was looted) wrote that many of Perkins’ sermons were heard all over the place as a result of the looted material being sold to clergymen. There is zero chance of finding it today! At one point I believed the Bedell might have left Perkins’ books at Trinity College Dublin, where he was the Provost for a period (1627-1629). That would have meant they are on the shelves in the photo below. I’ll have to find a different excuse to visit that amazing library!

Perkins spent his entire career in and around Cambridge. Various college archives still have original student notebooks from Perkins’ era, so I hope to discover evidence of Perkins influence and notes from these. That means I get to browse notebooks that are 400+ years old! Unfortunately I can expect much of the material to be in Latin, so that makes it more challenging. I am reasonably familiar with Perkins’ views, so I’m hoping I’m able to spot a ‘Perkinsism’ in a notebook when I see it.

Where am I going?

The sources I need to consult are located in London and Cambridge. I also plan to sight-see on some day-trips (e.g. Canterbury, Ely, etc). But here are the places that I need to visit for my work:

The British Library

It’s big and impressive, and it has boxes of letters from people who knew Perkins, and some theological notebooks.

The British Museum

OK, so I don’t need to go here for my research. But you need a reason to not go here as far as I’m concerned. I particularly want to see Tiglath-Pilesar III’s murals which show his failed attempt to capture Jerusalem (see Isaiah 37).

home of all the plundered treasures of the world

National Archives

There is a record here of a deposition (legal interview) that the authorities had with Perkins for his allegedly connections with that terrible group of people, the Presbyterians. Of course, they were actually good people. Some of them went to jail though! Elizabeth considered any challenge to the authority of bishops a short step away from challenging her own authority.

National Portrait Gallery

This is the home of basically all the Reformation portraits that double as covers for all of the books that I own. Every photo I see of the walls looks very familiar! There is also an original picture of Perkins here.

Cambridge University

Cambridge University is the air Perkins breathed for his entire adult life. I’m spending the bulk of my time in Cambridge to consult material in various locations there. Cambridge consists of a bunch of colleges with their own rules, libraries, archives, etc. That means I have lots of little colleges to visit rather than just one.

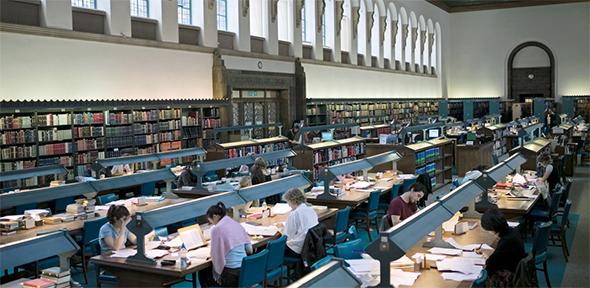

University Archives

The general university archives have notebooks, sermons, registers… most of what I need is stored here.

Christ’s College

This was the college Perkins attended as a student and then taught at. Then he left to get married and got a job directly across the road…

St Andrews the Great Church

Perkins preached at this church. When he was married in 1595 he got a job as ‘lecturer’ here, which means he was paid to preach in the afternoons. This isn’t the building Perkins preached in – that was two buildings ago. The original building was older than the university itself. I am so pleased to see an evangelical ministry thriving here today. I look forward to attending church here whilst I visit.

Corpus Christi College

Apparently Perkins catechised students here, but I’m not sure. There is an official record in this college’s archives of a university disciplinary trial from when (young hotheaded) Perkins preached against some ‘popish’ aspects of how the university conducted church. After that he seems to have concluded that this was too controversial and that he would focus on more important things (like preaching the gospel).

Emmanuel College

This is the key Puritan college, started in 1584 to train preachers of the Bible. Perkins’ tutor, Laurence Chaderton (1536-1640!), was its first Master.

Pembroke College

This cute college library has books in it that I have to read.

St Johns College

The ‘Old Library’ wasn’t begun when Perkins was around. It begun with the book collection of one of his editors, William Crashaw (1572-1626).

Trinity Hall

The registration of Perkins’ marriage is stored here. It might seem silly that these things are so spread out, but it does mean I have an excuse to visit some very interesting places!

Marsden Jabbett, Warwickshire

This is where Perkins was born. When he was born it consisted of 8 people and a cow. There are still 8 people living there, but the cow died. They now have electricity. I Google-toured it and decided it wasn’t worth a 3-hour bus trip.

Please pray that I have an enjoyable and very productive trip.