In Exodus 19 God’s presence arrived on earth in a way not experienced by humanity since the Garden of Eden (Genesis 1-2). God came to dwell with his people. I previously gave a brief overview of the Book of Exodus, followed by a tour of the Tabernacle. The Tabernacle is the grand climax of Exodus, though detailed descriptions of how to build the Tabernacle may seem pretty uninspiring on the surface. In this post we will look at some of the theology expressed in the structural details of the Tabernacle.

1. God’s Dwelling Place

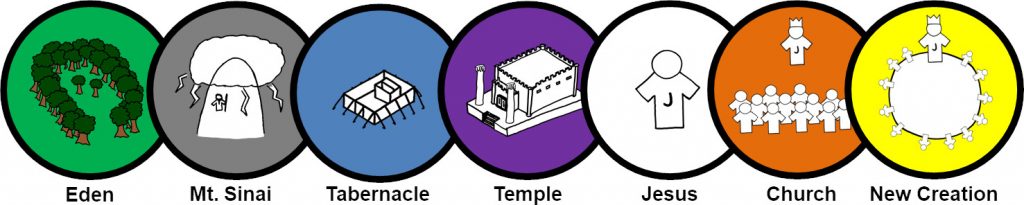

To begin with the big picture, the Tabernacle was the dwelling place of God among his people (Exodus 25:8). In fact, the word ‘tabernacle’ means ‘dwelling’. The Tabernacle was neither the first nor the last dwelling place of God in the Bible. It is part of a series of divine sanctuaries that progressively reveal God’s way of being present with his people in Jesus.

Eden was a kind of garden sanctuary in which God ‘walked’ (Genesis 3:8) but from which mankind was expelled for sinning (Genesis 3:23-24). Subsequently there is alienation between heaven and earth, between God and us. Although God continued to speak to people from heaven and to rule over history, he wasn’t directly present in the same way. In Exodus God came down to rescue and meet Israel at Sinai, which only served to show how deep the estrangement between God and sinners is. The Tabernacle was the portable version of Sinai by which God dwelt among Israel on their way to the Promised Land. Eventually the Temple was built in Jerusalem. It was a functionally-identical replacement for the Tabernacle. The main differences were that it was a permanent building and came with the promise of a unique Father-son relationship between God and the King of Israel (2 Samuel 7).

When Jesus arrived he fulfilled and superseded the Temple in every way. Whereas Old Testament sanctuary structures meant that God could come down to dwell among his people behind walls, now God became a human being in order to dwell among us directly. John’s gospel tells us that in the incarnation God ‘tabernacled’ among us (John 1:14). Jesus became the new place where God could be met on earth.

Jesus died, rose, and ascended into heaven to secure our salvation. He continues to be present with his people today through the Holy Spirit who personally dwells in Jesus’ people. This is why the New Testament speaks of Jesus’ Church as the temple of his presence in this age (1 Corinthians 3:16). When Jesus returns he will bring a New Creation, the entirely of which will be his dwelling (Revelation 21:3, 22).

Coming back to the Tabernacle, this was a new and unique promise to Israel: God was now with them. The presence of the Tabernacle preached this message to them every time they saw it. The priests were to ensure that the Tabernacle lamp alight from evening to morning (Exodus 27:21). This would have been the brightest light in the camp. It’s a symbol that meant the same thing to Israel as when we see a house with the light on today: the resident is at home. Israel’s God was always with them, as he is with us today (Matthew 28:20).

2. The Rule of the Invisible God

At the centre of the Tabernacle, in the Most Holy Place, sat the Ark of the Covenant. This was an ornate golden box with a solid-gold cover on it. This cover, or ‘mercy seat’, had two cherubim on it overshadowing the centre (Exodus 20:17-22). Any ancient person would have expected an idol figure of Israel’s God to appear here. It was the normal way people expected a deity to express their presence in the world. But Israel’s God (YHWH) could not be faithfully represented by a statue (such a feeble and domesticated ‘god’!). YHWH firmly forbid such ‘idolatry’ among his people (Exodus 20:4-6). It is striking that YHWH’s attendants – the Cherubim – are represented on the Ark but he is not. God is invisible and beyond created form.

Instead YHWH ruled from heaven through his words. The stone tablets engraved with the 10 Commandments were stored inside the Ark, representing YHWH’s rule through his law (Exodus 25:21). He would also continue speak to Israel from the empty space between the cherubim figures (Exodus 25:22; cf. Numbers 7:89). No statue could represent God in the world. The role of being God’s ‘image’ was exclusively given to mankind (Genesis 1:26). Israel were to fulfil this role by obeying God’s words.

Israel never saw the Ark. Few people did. When Israel travelled the Ark was carried by Levites at the head of Israel’s procession, as though a king leading his army (Numbers 10:33-35). When outside, the Ark was covered over by the curtain of the Most Holy Place, a leather cover, and finally a cloth of royal blue (Numbers 4:5-6). The Ark remained unseen by the people and shrouded in mystery. In this way it reflected the invisible nature of God and prevented the Ark being worshipped as though it was some kind of idol. YHWH was to be known by his words. The unique God of Israel was heard, not seen.

3. Holiness, Contamination, & Spiritual Biohazards

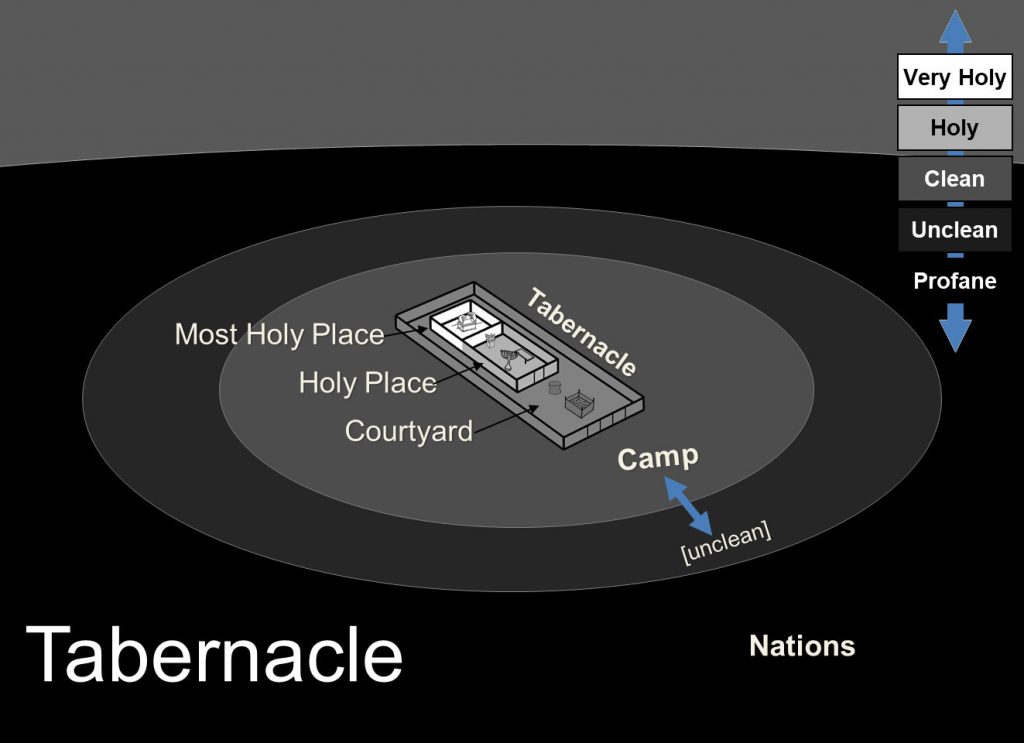

God’s holiness means that he is utterly pure. Holiness and uncleanliness are as incompatible as light and darkness: they literally cannot occupy the same space. The implication is that for anyone or anything to be fit for God’s presence it too must also be holy. However, as with physical filth, spiritual uncleanliness is contagious. Unclean things contaminate whatever they touch. That meant that the holiness of God’s dwelling was constantly under threat of contamination from the sinful Israelites living around it. The Tabernacle therefore consisted of a series of contamination containment zones that prevented holiness and uncleanliness from coming into contact with one other.

Holiness is associated not only with purity, but with righteousness, life, and wholeness. In the Bible God’s presence is violently opposed to uncleanliness, immorality, death, and disease. We might say that the Tabernacle was a massive Biohazard sign in the middle of Israel. But let’s be sure to get this the right way around. It isn’t that the Tabernacle was a biohazard; it is that the Tabernacle demonstrated to Israel that the world of fallen mankind was a biohazardous wasteland, full of death, disease, sin and idolatry. Somehow, someway, creation needed to be cleansed of sin and death and filled with holiness and life instead.

This worldview is foundational to the New Testament. When a leper approached Jesus for healing he asked “make me clean” (Mark 1:40-42). Healing and cleanliness essentially mean the same thing to Israel (Leviticus 13:8). They testify to humanity’s need for life and holiness, and for rescue out of our spiritually-biohazardous world of sin and death.

4. The Holy Mountain & Spiritual Geography

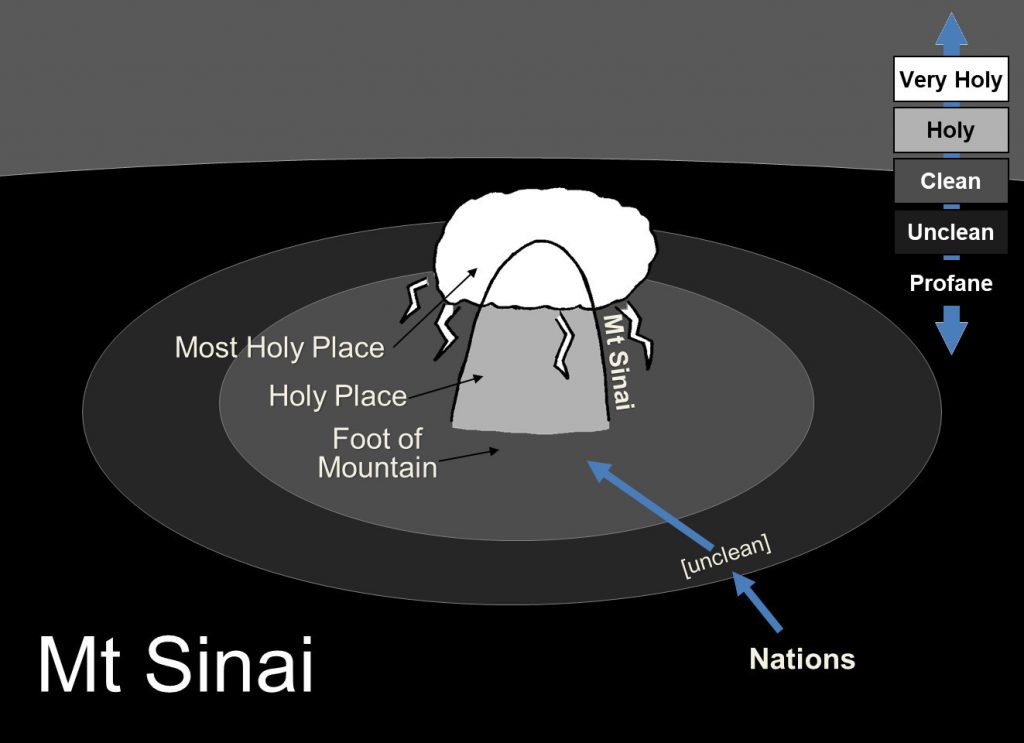

If you read Exodus 19 carefully you’ll notice that from the time Israel arrived at Mt Sinai there is an implied structure of buffer zones between them and God. These zones extend in concentric circles from God’s presence on the mountain outwards, moving from God’s pure holiness on the mountaintop toward the spiritual darkness of the nations.

Israel had been rescued from Egypt, the spiritually profane land of slavery and of false gods (Exodus 15:11, 18:11). They were brought to Mt Sinai, where Moses had first met his God and was informed that he was standing on ‘holy ground’ (Exodus 3:5). Israel were therefore to ‘cleanse’ themselves into a spiritually clean state before approaching God there (Exodus 19:10-11). That was the limit of their level of cleanliness. Israel were not to even touch the holy mountainside lest they die (Exodus 19:12-13). Moses alone was set aside by God as a mediator who could draw near to God’s presence. He proceeded up and down the mountain to communicate between God and his people. Once the covenant was established, representatives of Israel were invited up to eat a covenant-ratification meal in God’s presence on the holy mountainside (Exodus 24:9-11). But even here only Moses was allowed to enter God’s presence on the upper (most holy) regions of the mountain (Exodus 24:15-18).

It is important to recognise that even Moses didn’t have unlimited access to God’s presence. God was still in heaven (Exodus 20:22). At Sinai he had extended his holy presence into the world of sin and death, but heaven remained his dwelling. The summit of Sinai was a kind of heavenly outpost. Furthermore, even Moses was not allowed to actually ‘see’ God (Exodus 33:19-23). Any ‘seeing’ of God in the Bible (e.g. Exodus 24:11, 33:11; Isaiah 6:1) is of a strictly limited kind. Only Jesus has truly seen the Father and knows him without limit (John 1:18, 6:46).

This theme of the Holy Mountain continues in the Old Testament. If heaven is symbolically above us, then mountain tops seem the natural place to reach God. That is why humanity sought to rival God by building a tower to heaven (Genesis 11:1-9). The same impulse led the nations to seek out gods at ‘high places’; the peaks of Canaan was full of such idolatrous sanctuaries when Israel arrived there. Israel was commanded to urgently destroy these alternative ways to approach God (Deuteronomy 12:2-4). The God of the Bible will only be met on his own terms. All human attempts to reach heaven are doomed to failure and to God’s judgement.

When Israel built their temple on Mt Zion (Jerusalem) it became the highest place in the world. Not that Zion is a high mountain (you look down on it from the neighbouring Mount of Olives), but God’s temple is where heaven meets earth. The prophets later portrayed Zion as the tallest mountain on earth (e.g. Isaiah 2:2). A more subtle expression of this view is that when the Bible speaks of going to Jerusalem or the Temple, you always go “up” to it, never “down” (e.g. Matthew 20:17-18).

What does all this have to do with the Tabernacle? The Tabernacle teaches the same spiritual geography as the holy mountain. The Tabernacle tent, even when sitting in the middle of a flat desolate plain, was the highest point in the world. The foot of the mountain became a courtyard, the holy mountain-side became the first room of the Tabernacle, and the mountain-top became the Tabernacle’s inner-room, the Most Holy Place where God dwelt. The Ark of the Covenant reinforced this idea, being described as YHWH’s ‘footstool’ (1 Chronicles 28:2; Psalm 99:5; 132:7). The idea is that the holy God had breached the barrier between heaven and earth and, seating on his heavenly throne, had planted his feet on earth in the midst of Israel. Holiness on earth is defined in relation to God’s presence.

This way of looking at the world is not forgotten in the New Testament. God’s people are called ‘saints’ or ‘holy people’ (e.g. Ephesians 1:1; 5:27). This makes the church community the most holy place on earth, since by the Spirit they share in Jesus’ holiness and resurrection life. In contrast the world outside is darkness (e.g. Ephesians 5:1-14) from which God’s people must keep themselves from being polluted by (James 1:27). In keeping with this picture, the strongest form of church discipline is expelling an unrepentant professing-believer out from the church and into the realm of Satan. The goal is that they might (God-willing) see the catastrophe of their behaviour and repent (1 Corinthians 5:1-5, 11-13).

5. Eden Invades the World of Death

In many ways the Tabernacle is modelled on the Garden of Eden. The way the Bible describes the Tabernacle deliberately echoes the way the language of Genesis 2-3 to make this point. Both Eden and Tabernacle have a meeting place with God at their centre. Both have Eastward facing entrances (Genesis 3:24; Exodus 38:13). God ‘walked’ in the garden and ‘walked’ with Israel by means of the Tabernacle (Genesis 3:8; Leviticus 26:12). The Levites were told to ‘guard and keep’ the Tabernacle as Adam was with regard to Eden (Genesis 2:15; Numbers 3:7-8). The Spirit of God was involved in the construction of both creation and Tabernacle (Genesis 1:2; Exodus 31:2-6). Both were completed through seven “God said” actions (Genesis 1; Exodus 25:1; 30:11, 17, 22, 34; 31:1, 12). The completion of each work is related Sabbath rest (Genesis 2:2-3; Exodus 31:12-17). Just as “God saw that it was good” and blessed the seventh day (Genesis 1:31; 2:3), Moses’ saw Israel’s obedient completion of the Tabernacle and blessed them (Exodus 39:43). God ‘finished his work’ of making the cosmos, and Moses ‘finished the work’ (Genesis 2:2; Exodus 40:33). The creation of the Tabernacle echoes the creation of the world.

The Eden symbolism was particularly strong in the first room of the Tabernacle. Where Eden had a tree of life, the Tabernacle had a treelike lampstand, with branches, flowerlike-cups, buds, and blossoms (Exodus 25:31-36). It was essentially a tree with candles on it. When a priest looked toward the curtain barring entry into the Most Holy Place he would see two cherubim embroidered into it, staring back at him (Exodus 26:31-33). Just as cherubim guarded the path back to Eden (Genesis 3:24), the Most Holy Place was guarded by cherubim. Eden had re-appeared on earth but the way of return was still blocked.

The symbolic presence of Eden in the midst of Israel showed God’s intention to reclaim creation. When God met Israel he asserted ‘all the earth in mine’ (Exodus 19:5). The New Testament promises that one day all of creation will be reclaimed for life and holiness through Jesus (Romans 8:19-23).

6. The Route from Earth to Heaven

If from one perspective the Tabernacle is Eden, from another it is a model of creation as a whole. When you enter the courtyard you are in the inhabitable world of people, land animals, and the sea (cf. Genesis 1:10). Solomon’s temple would make this last point more explicit by labelling the bronze water basin the ‘sea’ (1 Kings 7:23-26).

Once you enter the first room of the Tabernacle, you have entered the visible skies. It is walled with blue fabrics and filled with a cloud-like haze from the incense altar. It is lit with a lampstand bearing seven ‘lights’ (cf. Genesis 1:14-18). These appear to symbolise the seven heavenly bodies visible to the naked eye: the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

When you get to the end of this room you reach the boundary between heaven and earth. The angelic figures on the curtain represent heaven beyond. Inside is a platform with angels overshadowing a throne which has no figure sitting on it. God is invisible, beyond created form, and yet present, ruling and speaking to his people on earth from his heavenly throne. Just as human beings cannot reach this God beyond creation, so no human being can enter past this point. The only exception to this gets to the heart of the gospel of the Tabernacle, which will wait for my next post.

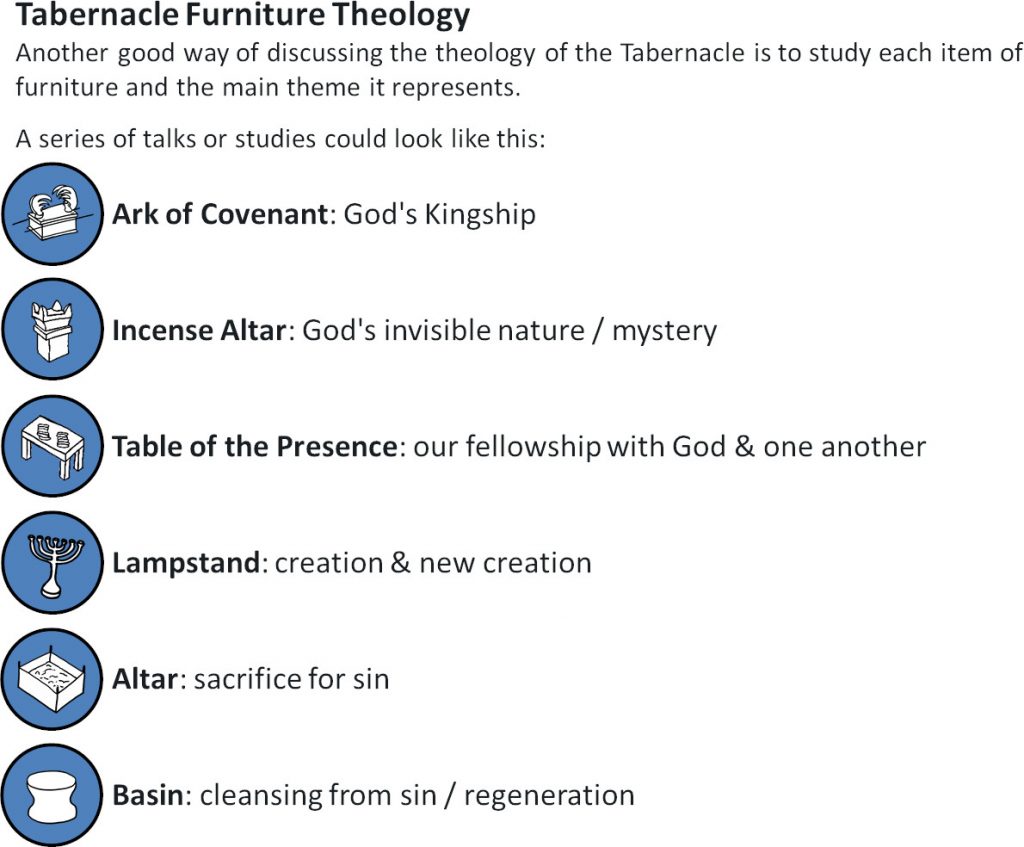

The Tabernacle is a model of all of creation, a cosmic roadmap of the impossible journey from earth to God’s presence in heaven. Our finiteness binds us to earth, and our sinfulness causes us to flee God’s holiness. It would take a special kind of priest that could enter into heaven itself on our behalf. Stay tuned…