I previously gave an overall positive review of Craig Hamilton’s Made Man (2019). This book offers a clear and interesting tour of why Jesus’ incarnation is essential to the Christian faith. One of my criticisms of the book was that I thought it could be improved by leaving out chapter 12, ‘Monothelitism or Dyothelitism?’. In that chapter Hamilton summarises what was at stake in the seventh century theological debate of whether Christ had one will (Monothelitism) or two wills (Dyothelitism). The latter view won out and continues to be widely held as a tenant of Christological orthodoxy today. Christ had two wills: one human and one divine. Hamilton presents this as the culmination of the Chalcedonian definition of Christ’s two natures, as championed by Maximus the Confessor (d.662).

About Maximus the Confessor

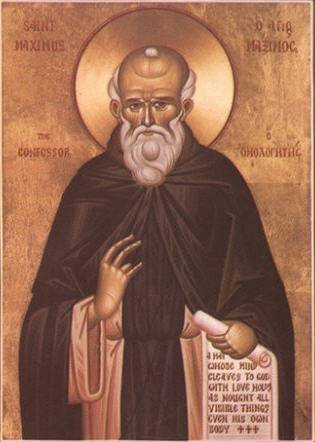

In the picture to the right you can see Maximus holding up two fingers. This indicates that he is a proponent of Christ having two wills (dyothelitism). Lots of earlier church fathers were painted in this pose at around this time as theological propaganda. In earlier years they didn’t debate this particular issue (it wasn’t raised yet), but of course we always know which side our heroes would have been on if they were here today, don’t we?

Maximus had his tongue cut out and his right hand cut off for his standing up for orthodox theology. Imperial theological politics were a dangerous business in those days! Maximus is rightly respected for his courageous stand for Chalcedonian orthodoxy, but that does not mean we should unquestioningly adopt his views.

So what concerns did I have with chapter 12?

First, I was surprised that the book delved into this difficult and controversial issue at all. For one thing, unlike the Christological teachings surveyed in earlier chapters, dyothelitism is not of the essence of ‘catholic Christianity’, as least as far as Protestants are concerned. That is, it is not among the doctrines expressed in the first four ecumenical councils which are unanimously agreed upon by mainstream Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox churches alike. For example, the doctrine statement of the Anglican Church (The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, 1571) asserts that the Nicene, Athanasian, and Apostles’ creeds are biblical and that all Christians ought to believe them (Article 8). The Nicene Creed here actually refers to the Council of Constantinople’s revised version (Fourth Ecumenical Council, 451), not the original from Nicaea (First Ecumenical Council, 325). That means that whilst confessional Anglicans are bound to believe the creedal conclusions of the first four ecumenical councils (which Hamilton covers in chs. 7-11) they are free to disagree with teachings agreed on in later councils (i.e. ch.12). The same point could be made with regard to other Protestant denominations.

Secondly, I was therefore disappointed that this chapter was framed in terms of what is ‘orthodox and biblical’ versus what is ‘heretical’ [p.183f.]. ‘Heresy’ is a severe term that is best reserved for teachings that undermine the Christian gospel (i.e. Galatians 1:9). I can’t see that a ‘monothelite’ understanding of Jesus undermines the gospel, at least not straightforwardly. At very least it depends on what is meant by the idea that Jesus had ‘one will’. That is especially relevant given that modern theologians often attempt to describe Jesus’ personhood in modern categories rather than assuming that late-patristic concepts are the best way of expressing biblical truth. There are a growing number of modern evangelical and Reformed theologians who reject Dyothelitism on biblical and philosophical grounds. I suspect that seventh century Dyothelitism and some modern ‘one will’ descriptions of Christ are actually saying very similar things, but in very different philosophical contexts. But that is a different topic (and a very large one!).

Third, there are very significant conceptual challenges involved in understanding Dyothelitism. This is easily the most challenging chapter in the book to understand, and it probably needed more than 11 pages to achieve its goals. I’m not convinced that this chapter is entirely consistent itself; at very least the terminology leads to confusion. ‘Will’ is a misleading term for modern English readers. In the seventh century it referred to an abstract set of desires that emerge from a nature. Jesus had two natures, divine and human, therefore his person experienced both kinds of desires and chose on the basis of what these sets of desires offered to him. Hamilton explains this well. But modern westerners use a late-medieval definition of ‘will’ which is very different than that which Maximus the Confessor worked with. Today we enthusiastically discuss ‘free will’ as a topic, which is about capacity to choose either way, even contrary to what we desire. For Maximus ‘will’ and ‘desire’ meant almost the same thing. As a modern believer, Hamilton himself appears to use the term ‘will’ in more than one way in this chapter, which leads to ambiguity and confusion. For example, when we read that: ‘The will of God is singular and the Bible never indicates otherwise’ [p.190], what exactly is meant? We need more information. Perhaps a terminological distinction could have made this chapter clearer. It asks too much of readers for them to attempt to think through multiple senses of the word ‘will’, and reach clear conclusions: “so… ‘wills don’t will things, persons do…’, but don’t persons will things with their wills? …”, and so on. In my opinion, Dyothelitism attempts to make confident assertions on issues that we should be very cautious about. The Bible doesn’t tell us how Jesus’ psychology functions.

Fourth, this chapter only engages with the Bible in a shallow way. Maximus the Confessor claimed that in Jesus’ prayer to the Father in the Garden of Gethsemane we see his two wills in conflict (Mark 14:36). Hamilton simply assumes that Maximus’ reading of the passage was correct without engaging in the kind of careful biblical exegesis displayed chapters 2-6. Many Bible readers (including myself) will remain unconvinced that the Gethsemane incident says anything about Dyothelitism. The narrative describes an interaction between two characters, Jesus and the Father. Jesus expresses that he doesn’t want to die and wants another way, but also resolutely commits himself to the Father’s will even if that means his death. (I’ve now mentioned three ‘wills’, namely two conflicting desires in Jesus, as well as the Father’s ‘will’, referring to his plan that the Son was following). Jesus wrestles with two conflicting desires within himself: his desire to not die (‘what I will’) and his desire (or will) to obey the Father’s will by dying on the cross (‘what you will’). Jesus having conflicting desires here is not unusual; all human beings experience ambivalence and competing desires at times. It isn’t obvious that we can ascribe one desire to the humanity of Jesus and the other to the divinity of Jesus. Maximus offers his theological interpretation of the passage, but it isn’t clear what compelling reasons we have to accept it, except “for Maximus told me so”.

Finally, this chapter points to what is missing from the book as a whole: Spirit-Christology. One of the most fundamental claims about Jesus in the New Testament is that he is the promised Spirit-bearing Messiah (e.g. Isaiah 11:1-5). This relates to Jesus being the ultimate King of Israel since the Messiah was the one equipped with God’s Spirit for his role (1 Samuel 16:13). However, it is also a deeply trinitarian point. The nature of Jesus’ existence and identity can’t be reduced to rightly formulating the relationship between his two-natures. Jesus is the eternally begotten Son of the Father, sent by the Father in the power of the Spirit. The three persons of the Trinity mutually indwell and depend upon one another. Jesus was incarnate by the Spirit (Matthew 1:18), anointed with the power of the Spirit (Luke 3:21-22; 4:1, 14, 18), did his miracles by the Spirit (Matthew 12:28; Acts 10:38), was resurrected by the Spirit (Romans 1:4; 8:11), and now lives the life of the Spirit (1 Corinthians 15:45). When Jesus returns we will share in his Spirit-filled resurrection life since we too have that same Spirit dwelling in us already (Ephesians 1:13-14).

These points are underemphasised in Hamilton’s book, mainly because they are underemphasised in patristic theology. (Well, mostly. In fact, some patristic authors were profoundly insightful on the Spirit, but the person of Christ was the focus of the era). Hamilton’s book is shaped by the Christology of the early councils and creeds, and therefore shares many of their strengths and weaknesses. Thus, it is almost entirely concerned with Logos-Christology, and says little about Spirit-Christology. The two-natures of the Son are expected to explain virtually everything about the who, what, and how of Jesus. The effect is that the Bible’s emphasis on role of the Holy Spirit in the who, what, and how of Jesus takes a backseat. Hamilton argues that the creeds are starting point from which to proceed further along the lines they lay out [p.180-1]. I agree. But even more important than that is considering how these things relate to the role of the Father and the Spirit in the who, what, and how of Jesus. That is what makes Christology trinitarian.

Spirit-Christology also explains how the incarnate Son can be a genuine example for Christians to follow and imitate (e.g. 1 Corinthians 11:1; Hebrews 12:1-3). Unlike Jesus we don’t have an underlying divine nature empowering our obedience. Rather, like Jesus, we have the Holy Spirit at work in us enabling us to obey God. Thus the incarnation in and by the Spirit means that Jesus can be a human example for all Christians to follow by the Spirit.

This is a critical post, so I want to end positively by reiterating what I said earlier. Made Man is a very good book that clearly, interestingly, and insightfully explains the debates about the nature of Christ’s incarnation that gave us the creeds we still use today. That makes this book valuable for all Christians who believe those creeds today.