“That’s a heresy!” It’s a line I’ve heard lots of times. I’ve not often been on the receiving end of this accusation, but I have noticed that it is sometimes thrown about rather freely. People often use it to refer to any teaching about God that they believe is untrue. Like many overused words, ‘heresy’ has become almost meaningless.

However, heresy is an important word that is worth using accurately. It has a long history in the Christian church, some good and some bad. But used rightly it goes to the heart of the gospel. It expresses what is at stake in knowing God truly, that is, as he has made himself known in his Son, Jesus Christ.

1. Heresy in the New Testament: Opposition to the Gospel

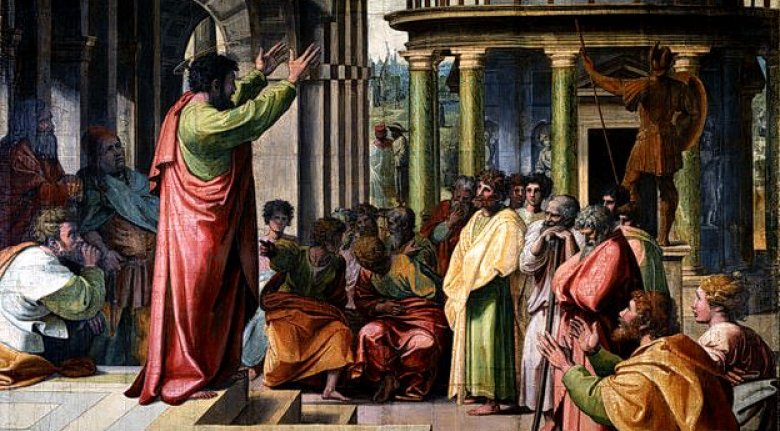

Probably the most important biblical passage for understanding the concept of ‘heresy’ is from the Apostle Paul:

Evidently some people are throwing you into confusion and are trying to pervert the gospel of Christ. But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel other than the one we preached to you, let them be under God’s curse! As we have already said, so now I say again: If anybody is preaching to you a gospel other than what you accepted, let them be under God’s curse!

Galatians 1:7-9 (NIV 2011)

The phrase ‘be under God’s curse’ (or ‘accursed’) is a translation of the Greek word anathema. In the following centuries anathema would become a technical term for false teachings that are so severely wrong that they lead to eternal condemnation.

That’s the basic idea in this passage too. Sinners can only find salvation by faith in the gospel of Jesus. If anyone twists or changes this gospel, or substitutes it with a different message entirely, then they will lead others to reject the true gospel, probably without their hearers even realising it. It’s like a doctor prescribing medicine that will cure a patient, only to have some renegade chemist sell lollies to the patient in a medicine bottle. You can label any bottle ‘medicine’ and any message ‘the gospel of Jesus’, but only real medicine cures and only the true gospel saves. In Paul’s letter to the Galatians, he confronts exactly this kind of situation. The Galatian Christians have come across teaching that threatens to lead them away from faith in Jesus without them even realising (Galatians 1:6-7). Paul responds by announcing God’s condemnation – anathema – on anyone who twists the true gospel in this way.

This kind of misrepresentation isn’t just a New Testament problem. Moses came down from Mt Sinai to find Israel worshipping a golden cow statute that they identified as the true God who brought them out of Egypt (Exodus 32:4). Likewise, most of the idolatry that Israel fell into in the Old Testament wasn’t an explicit rejection of God, but a distortion which added idolatrous ideas and practices to their religion. In the New Testament we read of people who ‘distort the Scriptures to their own destruction’ (2 Peter 3:16) or who ‘make a shipwreck of their faith’ (1 Timothy 1:19).

In short, a heresy is false doctrine that is damnable. It is any belief that leads to anathema, condemnation to hell. It is any message that undermines, replaces, or distorts the gospel into something it is not. Heresy is the gravest of all sins. It represents the biggest issue that Christians, and especially church pastors, must be on the lookout for as they guard the true knowledge of God revealed in Jesus Christ (1 Timothy 6:20; 2 Timothy 1:13-14; Jude 3).

2. Heresy in the Early Church: Opposition to Orthodoxy

We’ve seen that heresy is doctrine that is opposed to the gospel. Another way of expressing the same idea is that heresy is opposed to orthodoxy, meaning that it departs from core Christian doctrines.

Before long the early church discovered that it needed to officially clarify some of the more difficult theological questions that the gospel raises. Some of these questions are of enormous importance, such as the nature and identity of God and of his Son. These theological issues can be very intellectually taxing, but they also go to the heart of the gospel. It isn’t enough to just ‘believe the Bible’ – anyone can claim to do that whilst twisting it out of shape. The question is: what does the Bible mean?

So the early church councils sought to lay out explicitly what a true and biblical understanding of God involved. This is where we got the Nicene Creed from (325AD), and its expanded revision in 381AD. Church councils sought to summarise the biblical understanding of central theological issues so that the church could confess orthodox doctrine together with one voice (Romans 15:6). It also meant that they had a straightforward description of the faith against which they could spot theological error.

In each case the councils didn’t just affirm what was true, but explicitly highlighted known heresies as contrary to Scripture and the biblical gospel. The official pronouncements of the early councils would say things like: “if anyone says [INSERT FALSE TEACHING HERE]… let them be anathema“. These stern warnings urged people to attune their understanding of God to Scripture lest they get carried off into falsehoods that might undermine their salvation.

I can’t claim that these councils did a perfect job. They didn’t. Issuing strong, formal condemnations is an extraordinarily powerful act, and ought to be done with the utmost care and humility. The early church councils didn’t always succeed at that. However we should be thankful for the wonderful creeds and biblical insights that we have received from them.

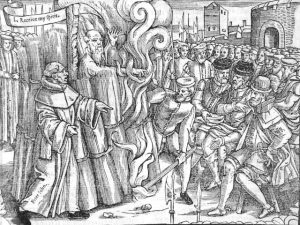

But then there are those horrible medieval developments. When some people hear the word ‘heresy’ today, they think less of the danger of hellfire, and more of the medieval practice of burning people to death for ‘heretical’ beliefs. Here ‘anathema’ became a weapon of condemnation, and even of state control. The tragic irony is that in the medieval period ‘heresy’ became disconnected from the gospel, both theoretically and practically. Jesus’ Apostles sought to convince others of the truth of the gospel through persuasion and argument, motivated by love. They warned of the consequences that God threatened for turning aside from the gospel. But there is no hint that heretics should suffer capital punishment. That is a deeply anti-Christian idea and is completely out of step with the gospel of grace. It is our place to warn, and even to expel sinners from the church when they refuse to repent (1 Corinthians 5), but the church’s power to judge extends no further than that.

Application

So how should Christians think about ‘heresy’?

First, we ought to think about it through the lens of love. Love of neighbour wants what is best for others. It leads us to warn others of danger wherever it exists, for their good. If people don’t believe in the true Jesus, revealed in the gospel, then they are in extraordinary danger. The same love that should motivate us to evangelise should also lead us to lovingly warn others of heretical distortions to that gospel wherever they exist.

Second, we shouldn’t throw the word ‘heresy’ around lightly. Heresy only properly applies to the worst form of false teaching: the kind that distorts the gospel and threatens salvation. We need to reserve the word for what it truly describes, lest we play out the story of “the boy who cried wolf” and find ourselves without the means to warn others in words that they will listen to.

An implication of this is that not all false teaching is heretical. People can commit theological error, and even contradict the Bible, without being heretics. That doesn’t mean that such false teaching is unimportant; it simply recognises that falsehood varies in its level of seriousness. To that topic we’ll turn next time.