Muriel Porter is well known for her scathing critiques of Sydney Anglicanism. The title of her books summarise a great deal about her grievances. The New Puritans: The Rise of Fundamentalism in the Anglican Church (2006) criticises Sydney Anglicans for not being progressive enough. Essentially the problem is that they take the Bible too seriously, especially on matters of sexuality and gender. However, an apparently opposite problem is that they are too progressive in a different way. Rather than holding fast to what Porter sees as proper ‘Anglicanism’ (robes, bishops, rigid use of Anglican liturgy, etc), Sydney Anglicans characteristically set these things aside for the sake of attempting to present the gospel to modern people in less culturally archaic forms. This is why Porter connects them to the ‘Puritans’ of the 16th and 17th century, those renowned opponents to Anglicanism who wanted to reform and change everything that made Anglicanism distinct. The scale of the threat Porter perceives is expressed in the title of another of her books: Sydney Anglicans and the Threat to World Anglicanism, 2011).

There are certainly some distinct, and even unique, characteristics of the Sydney Anglican diocese. However, this ought not to be exaggerated. Every Anglican province in the world has its own individual history and unique characteristics. But this post is not really about the Anglican Diocese of Sydney. Instead I am interested in answering the question that Muriel Porter assumes a particular answer to: what is the nature of true Anglicanism?

The Old Story about Anglicans and Puritans

This is a long disputed question. Every generation of Anglicans wants to claim that they are the genuine Anglicans and claim a set of heroes who best exemplify their preferred version. But what does ‘genuine Anglicanism’ mean? Can it ever be more than mere personal preference; the brash proclamation that “me and my tribe are the true Anglicans”?

I take it that the idea of ‘true Anglicanism’ must refer to the nature of the national English church as it was originally constituted when it broke from Rome and became its own entity in the sixteenth century. Its foundational, authoritative documents have remained constant throughout its history, though attitudes and interpretations of them have changed. The two most significant of these are its liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer (BCP, 1559, 1662), and its doctrinal statement, The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (Articles, 1563, 1571). These were officially introduced in Elizabeth’s reign and have been central to Anglicanism ever since.

Historians have long struggled to rightly describe the dynamics of this period, and how to properly label and characterise the people and parties involved. Words like ‘Anglican’, ‘Puritan’, and ‘Calvinist’ have long been debated, both regarding their proper meaning in this period, and also their relationship to one another. Let me tell you a common version of the story of the origins of Anglicanism and you’ll see what I mean.

Elizabeth I became queen in 1558, and her religious policy was introduced in 1559. Her ‘Anglicanism’ was broad, peaceable, and tolerant. What marked it out was its traditional liturgy, clerical vestments, and episcopal form of church government (i.e. bishops). According to this story, Anglicanism was a kind of ‘middle way’ (via media) between the extremes of Roman Catholicism and the Reformations of the continent, such as that of John Calvin in Geneva.

Problems with this arrangement arose when many of the more ‘enthusiastic’ Protestants, influenced by continental examples, relentlessly called for further reform of Elizabeth’s church. This group became known as ‘Puritans’ since they wanted to continue to ‘purify’ the church according to the Bible. In this story Puritans are the non-Anglican critics of the mainstream church, outsiders to what Anglicanism was all about. Their Reformed theology (i.e. ‘Calvinism’) is also seen as an alien intrusion into the broader, more ‘moderate’ English national religion.

On this understanding, Puritanism came into existence as a reactionary movement against Anglicanism:

Thus, by definition Puritans and Anglicans were ideologically at war with each other. That idea seems to fit well since in the next century the King of England and English Parliament would literally go to war against one another. It is has long been tempting to basically identify these two sides as the continuation of the “Anglicans vs Puritans” debate of Elizabeth’s era, with the hostilities gradually ramping up to exploding point.

A Few Problems with this Story

It is hard to overstate how utterly mistaken this view of early Anglican history is. Whilst there continue to be historical debates on many aspects of Elizabethan religious identities, the consensus has long been that this version of the story is simply wrong.

First, there is a language problem to overcome. ‘Anglican’ is a nineteenth century word invented by an Anglo-Catholic movement called ‘Tractarians’. Their mission was to redefine the history and nature of the English national church. The idea that the Church of England was a ‘middle way’ between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism was their invention. However, whilst ‘Anglican’ is a misleading word with regrettable historical baggage, it is the word we are stuck with. It now describes the church denomination that was once simply the national church of England, but which now extends throughout the world. We therefore need to distinguish two kinds of Anglicanism. Simply stated:

I use the word Anglican to refer to the Church of England as established and described in its foundational documents. “Anglican”, in contrast, refers to more recent set of emphases that were never part of the Elizabethan settlement, such as a vague ‘middle-way’ theology and strong emphases on old fashioned liturgy and ceremony, clergy in traditional vestments, and the oversight of bishops. We shall see that “Anglicanism” is not Anglicanism. The terminology is confused but please note it carefully – this distinction is crucial to what follows.

Second, the doctrine statement of the Church of England (The Thirty-Nine Articles) clearly teaches Reformed theology. From the start, Anglican theology was Reformed (i.e. ‘Calvinist’). Among other things it teaches that:

- the Bible alone is the authoritative source of doctrine,

- Christ’s death alone atones for sin,

- we are saved by faith in Christ and not works,

- people can only respond to Christ with faith by the gracious enabling of the Holy Spirit,

- recipients of this saving work were predestined to it by God,

- that Roman Catholicism is emphatically and utterly wrong on issues of salvation.

This is true Anglican theology. Early Anglicans were not wishy-washy, and they weren’t afraid to criticise false beliefs.

Third, Puritans and Anglicans were not clearly distinguishable groups. Puritanism was more of a disposition than anything. They were “the hotter sort of Protestant”; enthusiastic English Christians whose commitment to biblical truth led them to champion the theology of the church, and also challenge it where they saw it in need of further reform. This impulse led a few to leave the institutional church, but most Elizabethan Puritans were insiders to the English church, not outsiders. As an important recent study on early-modern English piety argues:

‘…the division between puritan and conformist Protestants, which has been so important in English historiography, almost fades from view when examined through the lens of devotion and lived experience.’

Alec Ryrie, Being Protestant in Reformation Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 6.

Or, according to the definitive historical study of Elizabethan-era Puritanism:

‘That our modern conception of Anglicanism commonly excludes puritanism is… a distortion of our religious history…’

Patrick Collinson, The Elizabethan Puritan Movement (London: Methuen, 1967), 467.

Fourth, whilst liturgy, clerical vestments, and episcopal oversight might seem to be the most distinct things about Anglicanism now, officially they were some of the least important. These matters of outward style and organisation were technically categorised as adiaphora, meaning ‘things indifferent’. Such matters were regarded as things which the Bible doesn’t make clear prescriptions about. Christians therefore have freedom to order these matters as seems most beneficial to edification and the good order of the church. Of course, most Puritans didn’t agree that issues like church governance was adiaphora; most of them thought the Bible required Presbyterian church governance. Furthermore, and what is shocking to modern sensibilities, in practice adiaphora didn’t mean that everyone was free to do whatever they wanted where Scripture was silent. Rather, it meant that the queen had the right to legislate matters of adiaphora in the national church as part of her governance of the nation. That is, Queen Elizabeth had the right to insist that church be conducted according to the Book of Common Prayer, that the clergy wear traditional vestments, and that the governance of bishops be retained. After all, these were officially categorised as matters relating to maintaining social order, not to faith itself, so weren’t considered spiritually significant.

Puritan Tensions with Elizabeth’s Settlement

So there was real tension between Puritanism and the Queen’s unwillingness to consider possible changes to her church settlement. But notice the topics of disagreement: they were matters ‘indifferent’, and not core theological issues. In general we can say that Puritans championed two things:

- Further reform of English churchmanship: clerical vestments, liturgy, and episcopal church governance.

- Enrichment of English piety, especially through biblical preaching.

On the first they had no success. Anglicanism retained its distinct outward forms because the queen wanted it that way. On the second point there was less tension: Puritans simply sought to preach, teach, and promote the Reformed theology and piety enshrined in Elizabeth’s religious settlement. Here they were simply good conforming Anglicans, faithfully and energetically getting on with the work of the church.

In fact, Puritans were often the most conscientious and productive Anglicans of their day, providing the established church with many of its best pastors. For example, the founding of both Emmanuel College (1584) and Sidney-Sussex College (1596) in Cambridge were Puritan endeavors, intended to supply well-trained preaching ministers for English parishes. In many ways, Puritanism was the engine-room of English pastoral ministry. In the judgement of the greatest historian of Elizabethan Puritanism:

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that [Puritanism] was the real English Reformation.

Patrick Collinson, The Reformation (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003), 117.

Puritanism & the Invention of “Anglicanism”

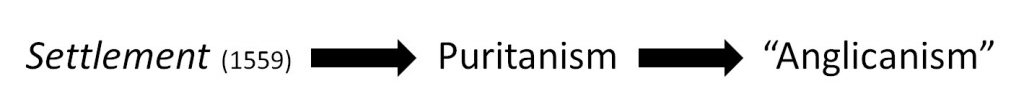

Above we recounted a common mistaken idea that Puritanism came into existence as a reaction to “Anglicanism”. In fact, it is far more historically accurate to say that “Anglicanism” came about in reaction to Puritanism.

Basically, Puritan conformists got on with preaching and pastoring in accordance with the official Reformed religion of the nation. In reaction to to their success, “Anglicanism” emerged in the 1580s-90s. Two key shifts are important:

- Various issues of adiaphora were transformed into core issues, especially liturgy, ceremony, and the role of bishops.

- Many people sought a more ‘moderate’ and ‘reasonable’ version of Christianity, a ‘mere conformity’ rather than the passionate commitment and piety of so-called ‘Puritans’.

Both of these shifts represent departures from the founding principles of Anglicanism.

First, whereas episcopal church governance was originally considered a matter indifferent, several influential clergymen began claiming that bishops were the form of church government which God commanded [1]. Similarly, some developed what we would call ‘high church’ liturgical practices, emphasising solemnity, ‘beauty’, and ceremony, and claiming that liturgical style was not a matter indifferent [2]. What we see here has been called the invention of “Anglicanism”; a set of innovations contrary to the founding principles of the English Church!

The second change was the growing sense that lots of English people didn’t want to take Christian devotion as seriously as those ‘Puritans’ did. As today, a lot of people didn’t really care about the Bible or church all that much. They wanted a ‘mere conformity’ of basic belief, morality, and church-going that didn’t involve enthusiastic devotion to God. This kind of easy-going nominalism was perhaps inevitable in a national church, but we need to recognise that it was entirely out of step with official Anglican theology. On this point, Puritan ‘enthusiasm’ is the true Anglicanism.

In short, the style of religion often called “Anglicanism” today is a departure from the foundations of genuine Anglicanism. “Anglicanism” has literally turned ‘matters indifferent’ into core values, and points of distinction and emphasis. At the same time, central matters are often forced to the margins: justification by faith alone, the sufficiency of Christ’s atoning death for sin, the urgent call of the gospel to all people to repent, and so on. These were the doctrines that Anglicanism was built on and which are enshrined in its confession of faith.

In my view, this is a great tragedy. But, even if you don’t share my personal reaction, the historical fact remains that Puritanism was (and is) far more genuinely Anglican than what has come to be known as “Anglicanism”. Contrary to Muriel Porter and others like her, if modern “Anglicans” were to became more Puritan, they would find themselves being more authentically Anglican than they ever were before.

References

[1] The first major work defending episcopacy as divinely ordained was John Bridges’ massive volume A Defence of the Government Established (1587).

[2] The landmark text that transformed matters of ceremonial style from adiaphora to practices possessing intrinsic spiritual was Book 5 of Richard Hooker’s Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1597). Other key names include Lancelot Andrewes and John Overall.

Further Reading

The best place to read serious history of the relationship between Puritanism and Anglicanism is the work of Peter Lake. His contribution to the new Oxford history of Anglicanism is particularly useful:

Peter Lake, ‘‘Puritans’ and ‘Anglicans’ in the History of the Post-Reformation English Church’ in The Oxford History of Anglicanism. Volume 1: Reformation and Identity, c.1520-1662 (ed. Anthony Milton; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 352-379.

Peter Lake, Anglicans and Puritans? Presbyterianism and English Conformist Thought from Whitgift to Hooker (London: Allen & Unwin, 1988).

Peter Lake, Moderate Puritans and the Elizabethan Church. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

On the emergence of “Anglicanism” I also recommend:

Peter Lake, ‘”The Anglican Moment”: Richard Hooker and the Ideological Watershed of the 1590s’ in Anglicanism and the Western Christian Tradition: Continuity, Change Communion. (ed. Stephen Platten; Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2003), 90-121.

Anthony Milton, ”Anglicanism by Stealth’: The Career and Influence of John Overall’ in Religious Politics in Post-Reformation England: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Tyacke (eds. Kenneth Fincham & Peter Lake; Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2006), 159-177.

Nicholas Tyacke, ‘Lancelot Andrews and the Myth of Anglicanism’ in Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church, c. 1560-1660 (ed. Peter Lake & Michael Questier; Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000), 5-33.

A great deal of the new “Anglicanism” of the late-Elizabethan era had to do with what historians now call ‘avant-garde conformity’. On this I recommend:

Peter MacCulloch, ‘‘Avant-Garde Conformity’ in the 1590s’ in The Oxford History of Anglicanism, 380-394.

Kenneth Fincham & Nicholas Tyacke, Altars Restored: The Changing Face of English Religious Worship, 1547-c.1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 74-125.