COVID-19 has forced churches to cease their regular church services for the moment. Christians are rightly eager to do whatever they can to help prevent the spread of the virus. That presently includes not only foregoing public church gatherings, but even smaller Bible study groups.

Physical proximity is essential to what the Bible means by ‘church’ (the word literally means ‘gathering’). In the absence of physical gatherings, people have been able to ‘gather’ online. Whilst physical proximity has been lacking, personal connection has not. ‘Zoom’ appears to be the platform of choice for Bible study groups and even entire congregations. Many churches have started their own YouTube channels to broadcast sermons and services to Christians in their homes. A whole new set of practices has been forced on churches overnight. (Be kind to your pastors – they are likely struggling with managing these challenges!).

This is far from an ideal situation, yet we have a lot to be thankful for. It appears that in our modern world Christians can enjoy a relatively rich corporate life even in isolation, via various online platforms. Technology is a wonderful tool that can facilitate genuine gospel ministry which will be of spiritual benefit to those who participate in it.

But what about the Lord’s Supper?

The Lord’s Supper (or Eucharist, Holy Communion) doesn’t translate to the online world so easily. It involves physically sharing in a meal together: drinking the same drink and eating from the same loaf of bread (Mark 14:22-25; 1 Corinthians 11:17-33). You can’t do that via a webcam!

And yet I believe that we can and should conduct the Lord’s Supper in our present circumstances. This will be particularly fitting if isolation continues for an extended period. The Lord’s Supper is a valuable part of the Christian life. It enriches our faith and sense of unity in Christ. Whilst there are dangers to avoid, I believe that it can be practiced over the internet responsibly and in a spiritually beneficial way.

The Lord’s Supper is a physical embrace of the gospel and of one another in Christ. In it we are called upon to recognise ‘the body of the Lord’ (1 Corinthians 11:29), an idea with a deliberate double-meaning. Most obviously, it refers to Jesus’ physical body in which he was crucified on a Roman cross to accomplish the forgiveness of our sins. Yet in another sense Christians together make up the ‘body of Christ’ (Ephesians 4:15-16).

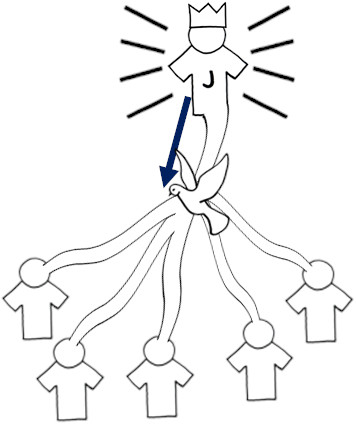

When we turn to Jesus in faith, the Holy Spirit unites us to Jesus and the life that is in him. The Spirit acts as a conduit by which the life of Jesus is shared with us; an unbreakable tether that joins us to him. An implication of this is that Christians are also united to one another by means of their union with Christ by the Spirit. It is impossible to be united to Christ without being united to all his people at the same time.

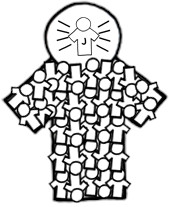

This truth the basis of the ‘body of Christ’ image. Together Christians are the ‘body of Christ’, and Jesus is the head (Colossians 1:18). If it helps, we should envisage Christ’s ‘body’ as a giant composite man made up all believers, a bit like Voltron, or Power Rangers (depending on your age bracket). God calls upon his people to maintain and express this unity that he has created in his Son (Ephesians 4:3).

In the Lord’s Supper we recognise and express our union with Christ and (through him) our unity with one another. The reason that the Apostle Paul had to instruct to the Corinthian church about the Lord’s Supper wasn’t because they failed to recognise Christ, but because they were failing to recognise one another as Christ’s body (1 Corinthians 11:18-21, 33; 12:12-30). Both the ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ aspects of this union are essential to the Lord’s Supper.

Three Core Truths in the Lord’s Supper

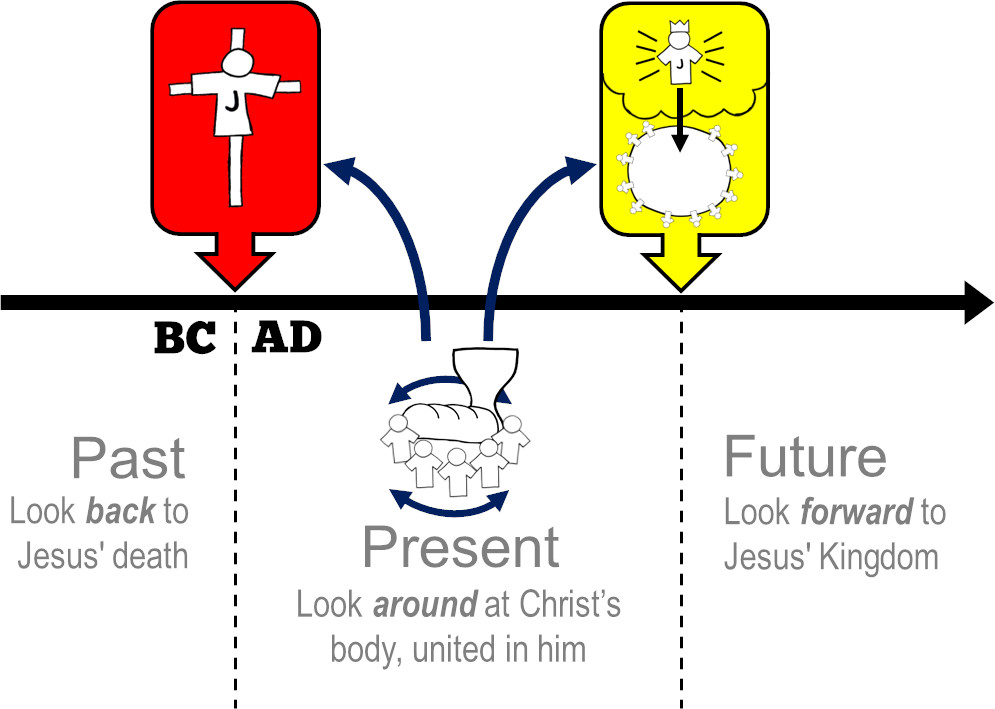

We might say that participating in the Lord’s Supper should lead us to focus on three things. First, we recognise the death of Christ in the past: that by his blood we are saved and made members of his body (1 Corinthians 11:23-35). Second, we recognise one another as members of his body in the present, united together by the Spirit. Third, we look to the future coming of the Kingdom of God, the kingdom which Jesus’ death brought into being and which we will share with him and with one another when it arrives (1 Corinthians 11:26). It should be clear that the Lord’s Supper is a rich experience of the gospel. It proclaims all the God has done for us in Christ.

The Lord’s Supper involves sharing together in physical bread and wine to symbolise our unity. It is only natural, therefore, that the proper occasion upon which to celebrate the Lord’s Supper is ‘when you gather’ as a church (1 Corinthians 11:20). Indeed, that is the case.

However, in a time when the church is not able to gather, it doesn’t necessarily follow that we are not able to share the Lord’s Supper together at all. Indeed, at a spiritual level, our physical proximity to one another is of comparatively low importance to what it involves. The Lord’s Supper involves personal communion with Christ and one another. Personal community and mutual recognition of one another in Christ can be experienced in a meaningful way online through software like Zoom or Microsoft Teams. It isn’t an ideal situation, but it doesn’t involve any serious theological problems that I can see. In fact, the Lord’s Supper should remind and encourage us that our lack of physical proximity does not hinder our unity in Christ. The Holy Spirit unites us to Christ and to one another just as capably whether we are sitting in the same room or can only see one another through webcams. In either situation our unity in the blessings of the gospel should be shared and enjoyed together.

But what about the physical elements?

The physicality of the Lord’s Supper powerfully testifies to our dependance on Christ. Jesus said: “this is my body – eat” and “this is my blood – drink”. Christians eat and drink Christ into themselves. It’s a meal. By eating and drinking we physically nourish and strengthen our bodies by food. Yet in this case, we also nourish and strengthen ourselves spiritually by Christ.

This recalls Israel being fed manna and quail in the wilderness (Exodus 16). God provided the Israelites with sustenance for their journey to the Promised Land. Likewise, Christ is our sustenance for the journey to the heavenly Promised Land (1 Corinthians 10:1-6, 16-17; John 6:32-35, 48-58). The Lord’s Supper strengthens us to persevere. This is why the Lord’s Supper is traditionally described as a ‘means of grace’ (alongside baptism and preaching): it is a practice by which the Holy Spirit kindles faith and obedience in his people. This is why we should hesitate to neglect it at the present time. God’s people need to experience God’s gospel promises together, even if by webcam.

Of course, that means that we won’t literally be eating from ‘one loaf’ together in this circumstance (1 Corinthians 10:17). The symbolism of ‘one loaf’ obviously relates to the way that the supper communicates our being ‘one body’. How much does sharing in the same loaf matter?

Here we get to the classic debates about the Lord’s Supper. Jesus’ phrase ‘this is my body’ (Mark 14:22) is surely one of the most energetically discussed phrases in the Bible. The amount of theological argument that has been written about it could easily fill a library of enviable size (though it is unlikely to a library of enviable contents).

When it comes to doing the Lord’s Supper from a distance, Protestants do not have the theological problem that Roman Catholics have. According to official Roman Catholic teaching, the bread and wine of the Eucharist are literally changed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ when the priest declares ‘this is my body/blood’, elevating them to indicate the ‘miracle’ of the Mass. This is called ‘transubstantiation’. It means that Jesus is (allegedly) made physically present in the church building so that those present can partake of him. In this scenario you need to be physically present to spiritually benefit.

Protestants rightly reject this teaching as unbiblical. Here the Anglican view can be taken as representative of Protestant and Reformed views in general. When Thomas Cranmer wrote the Book of Common Prayer (1549, 1552), he changed the Lord’s Supper service so that it was clear that there was no transformation of the elements involved. They are merely symbols. The real spiritual action is what occurs in the hearts of all those who ‘rightly receive’ Christ by the sacrament, that is, by faith. Rather than lifting the bread, the people are urged to ‘lift up your hearts’ in thanksgiving for the salvation given in the gospel. When they receive the elements to consume they are told to ‘feed on [Christ] in your heart, by faith, with thanksgiving’. The spiritual ‘eating’ and ‘drinking’ of Christ doesn’t happen by the act of consuming food and drink, but in those hearts which truly receive Christ by faith. As the Anglican statement of faith says:

‘…to such as rightly, worthily, and with faith, receive [them], the Bread which we break is a partaking of the Body of Christ; and likewise the Cup of Blessing is a partaking of the Blood of Christ.’

Article 28, The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (1563, 1571)

The Reformers recognised that the Lord’s Supper was most fittingly celebrated by the gathered church. But they also realised that, since the core spiritual action is in hearts and not on a table, it did not need to be locked away in the church in all circumstances. Thus, the Book of Common Prayer includes instructions on how to conduct ‘Communion of the Sick’. Here a minister would visit the dwelling of a person too sick to attend church in order to encourage them with the gospel and share the Lord’s Supper with them. This is good pastoral sense in practice. The same applies to a situation where none can physically gather. It is completely appropriate for God’s people to have a second-best version for those who can’t get to church – all of us at present! Let’s not forget that the Lords Supper was made for the Church, and not the Church for the Lords Supper.

How to do the Lord’s Supper from a Distance

So how would you do the Lord’s Supper online? I’ll leave pastors to work out practicalities themselves, but at very least the following appear important:

- The Lord’s Supper is a meeting of God’s people, not a TV show to watch on replay later. It needs to be practiced personally, which means by people who are personally engaging with one another. It should involve those participating being able to see and engage with one another. A video-conference call does this well.

- Whatever the circumstances, the Lord’s Supper involves two kinds of preparation. First, people need to have appropriate supplies ready at home: bread and wine/grape juice. Random choices of food and drink aren’t fitting substitutes (for reasons we can’t explore here). Second, and more importantly, they need to be prepared spiritually. The Lord’s Supper is anything but a trivial observance (1 Corinthians 11:29). It should involve sober reflection, not last-minute, distracted engagement. Pastors will need to instruct and lead their people here.

- If your church chooses not practice the Lord’s Supper during this time, don’t stress. Respect the decisions of your leaders (Hebrews 13:17). There are any number of possible reasons for which they might consider this practice to be unhelpful in the church which they oversee. If you personally aren’t comfortable to participate in this way, don’t – but don’t judge those who do either (cf. Romans 14:4, 6). The opposite likewise applies. The Lord’s Supper, of all things, should not be a cause of disunity.

And after the Virus…

So what about when (God-willing) COVID-19 dissipates and we are allowed out of our houses again?

At that point I believe that we ought to cease online Communion services again. It is supposed to be practiced in the gathered church. What I suggest here is a contingency plan intended for the very unusual circumstances we find ourselves in.

It’s also an opportunity to rethink something important from a new perspective. If nothing else, I hope that thinking this through has helped you to appreciate anew our unity in Christ, and the spiritual value of the Lord’s Supper.